Image 1 of 3

Image 1 of 3

Image 2 of 3

Image 2 of 3

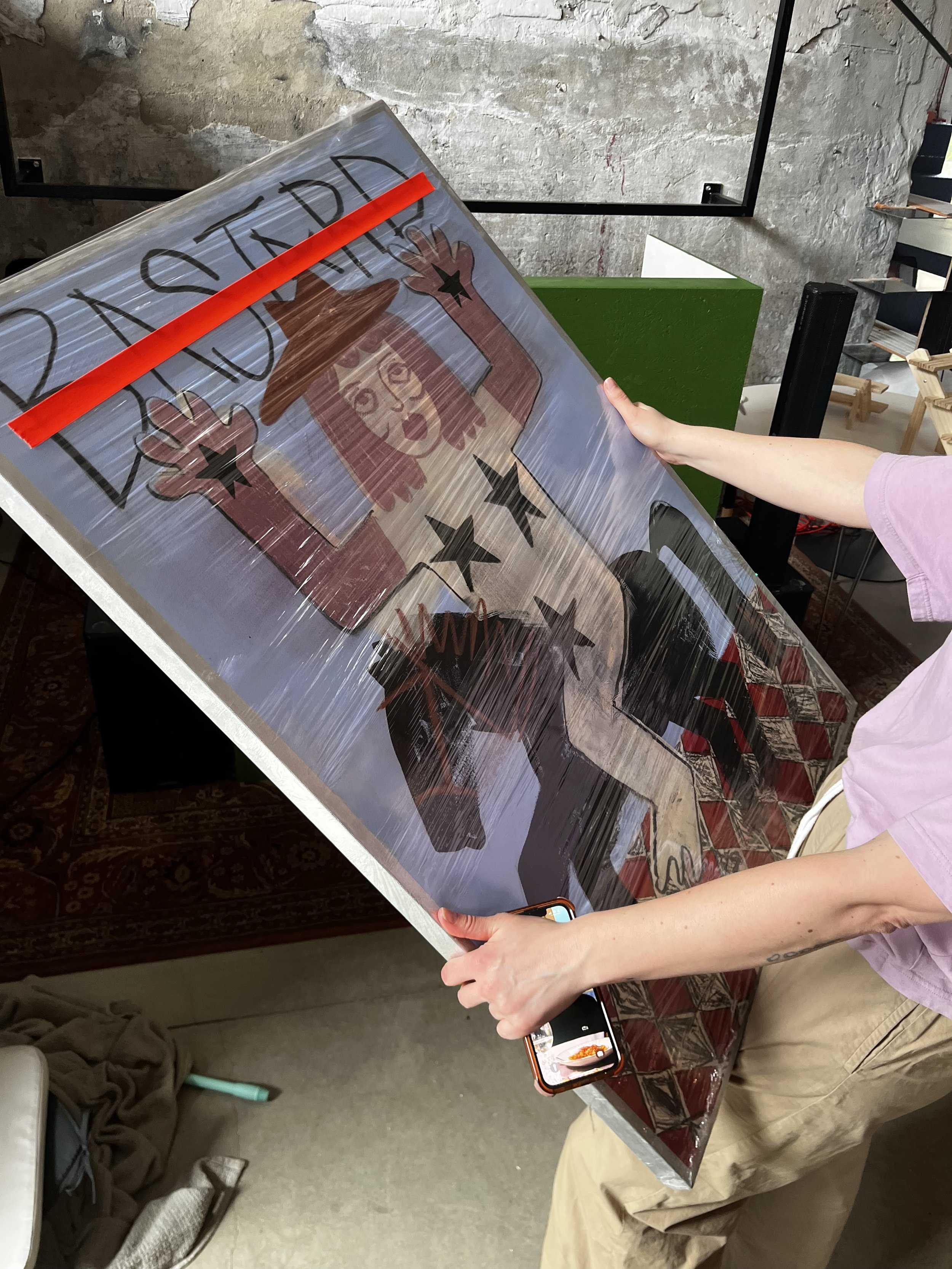

Image 3 of 3

Image 3 of 3

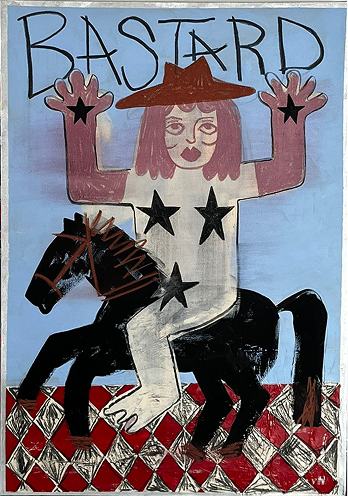

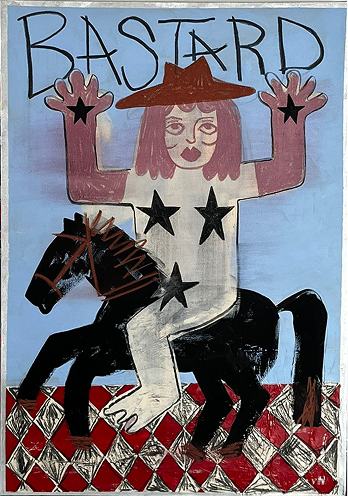

BASTARD

100 × 70cm

39.4 × 27.6in

Acrylic, oil pastels, and collage on canvas. Shipped unframed. Fully insured shipping via DHL.

This sale is active only during February 1–28

All sales are final. This is a limited studio sale with discounted pricing. Shipping is scheduled for the first week of March and is not immediate. No refunds, returns, or exchanges will be accepted.

BASTARD - the beginners blessing

The first thing you see is not the words, the insult. You notice the blue sky, the baby’s blocky limbs, the cartoon horse, the funny hat… The composition feels playful, like the things I used to scribbled on my school desk.

I started the Baby Series as an intentional exercise in fighting perfectionism, going against my own expectations, my maturity, and allowing the imperfect inner-child to come through. Right around the time I painted the first Baby in the series, I was reading a book of essays, interviews, and collected thoughts from the abstract painter Philip Guston. In it, he describes an exercise: when painting, he intentionally moves against the direction his brain tells him to go. If his mind says “go right,” his hands will deliberately go left.

In my whole life, from what I can recall, I never had the courage to be so rebellious, so courageous.

Painting with naïveté is far harder than painting with skill. I believe Picasso was the one who famously stated, "It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child".The difficulty of achieving artistic innocence and originality compared to mastering technique can be extraordinary.

With a child like painting the limits aren’t clear; you have to find them as you go, discover the boundaries as you paint. It’s an exploration, a kind self-satisfaction that becomes very complex to bring on to the surface, especially because you are creating something that inevitably has so many hidden expectations.

So for you to paint like a child you have to fight your instincts. You have to actively remember the feeling of an unfiltered pride you remember feeling when you were a kid and finished drawing a simple picture.

The flat colors in this painting and unshaded shapes have the ease of a drawing done without looking, fast and instinctual, without judgement. The hands are marked with stars, the body pale and almost paper-like, all of it rendered without pretension toward realism. Without any pretension at all.

This naïveté disarms. It brings us closer because we feel safe.

And then the word BASTARD.

It’s not just text; it sets the tone between the dichotomy of maturity and naivete.

It was my way of recalling the cruelty of children, the playground taunts, something that in my experience has left me with many scars, but also the centuries-old weight of illegitimacy as a social sentence. A bastard is someone born outside the sanctioned order, someone whose very existence is branded as wrong.

In a child’s world, the word stings without much comprehension. Children are walking talking voice recorders, they repeat what they hear around them.

In an adult’s world, it can dictate the course of a life.

Here, it hangs above the figure like both a curse and a crown, as myself I have seen many bastards wear it.

The tension between the style of imagery and the choice of language creates a split-screen experience, a kind of dynamic I often use in my work. The child side of me might see a cowboy free riding into a checkered sunset, again, a kind of imagery I am a big fan of. And the adult side might see a figure navigating through life with a black horse of shadow and instinct, anonymity and distinction, both seen and unseen.

But more than aesthetic irony, this piece can be read as an act of defiance. To paint in a style that knowingly refuses sophistication is to reject the hierarchies that privilege technical mastery over emotional truth. I like to think of it as the beginner’s blessing.

The so-called “childish” aesthetic becomes a tool, a way of smuggling grief, rage, and alienation into a form legible to anyone, regardless of their fluency in the art world’s codes. It says: You don’t need to be trained to speak; you only need to have something to say.

Perhaps that is what I meant when I began this whole BABY series, I meant to find a a way to remind myself of the this blessing, to return to how I first learned to paint, to remember what makes me different.

In this way, the painting becomes a form of personal reclamation. The figure doesn’t hide from the label; it rides beneath it, hands raised, stars branded into their skin like constellations they own. The horse carries them forward, not toward redemption or acceptance, but toward a place where insult becomes identity, where illegitimacy becomes freedom. Toward maturity.

Some say that as we grow older, we find more ways to bring out the child within us, more ways to hold hands with the innocence of what we once were, and how we once saw the world. I hope that whenever I feel like I’m close to forgetting, I remember to paint another Baby.

100 × 70cm

39.4 × 27.6in

Acrylic, oil pastels, and collage on canvas. Shipped unframed. Fully insured shipping via DHL.

This sale is active only during February 1–28

All sales are final. This is a limited studio sale with discounted pricing. Shipping is scheduled for the first week of March and is not immediate. No refunds, returns, or exchanges will be accepted.

BASTARD - the beginners blessing

The first thing you see is not the words, the insult. You notice the blue sky, the baby’s blocky limbs, the cartoon horse, the funny hat… The composition feels playful, like the things I used to scribbled on my school desk.

I started the Baby Series as an intentional exercise in fighting perfectionism, going against my own expectations, my maturity, and allowing the imperfect inner-child to come through. Right around the time I painted the first Baby in the series, I was reading a book of essays, interviews, and collected thoughts from the abstract painter Philip Guston. In it, he describes an exercise: when painting, he intentionally moves against the direction his brain tells him to go. If his mind says “go right,” his hands will deliberately go left.

In my whole life, from what I can recall, I never had the courage to be so rebellious, so courageous.

Painting with naïveté is far harder than painting with skill. I believe Picasso was the one who famously stated, "It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child".The difficulty of achieving artistic innocence and originality compared to mastering technique can be extraordinary.

With a child like painting the limits aren’t clear; you have to find them as you go, discover the boundaries as you paint. It’s an exploration, a kind self-satisfaction that becomes very complex to bring on to the surface, especially because you are creating something that inevitably has so many hidden expectations.

So for you to paint like a child you have to fight your instincts. You have to actively remember the feeling of an unfiltered pride you remember feeling when you were a kid and finished drawing a simple picture.

The flat colors in this painting and unshaded shapes have the ease of a drawing done without looking, fast and instinctual, without judgement. The hands are marked with stars, the body pale and almost paper-like, all of it rendered without pretension toward realism. Without any pretension at all.

This naïveté disarms. It brings us closer because we feel safe.

And then the word BASTARD.

It’s not just text; it sets the tone between the dichotomy of maturity and naivete.

It was my way of recalling the cruelty of children, the playground taunts, something that in my experience has left me with many scars, but also the centuries-old weight of illegitimacy as a social sentence. A bastard is someone born outside the sanctioned order, someone whose very existence is branded as wrong.

In a child’s world, the word stings without much comprehension. Children are walking talking voice recorders, they repeat what they hear around them.

In an adult’s world, it can dictate the course of a life.

Here, it hangs above the figure like both a curse and a crown, as myself I have seen many bastards wear it.

The tension between the style of imagery and the choice of language creates a split-screen experience, a kind of dynamic I often use in my work. The child side of me might see a cowboy free riding into a checkered sunset, again, a kind of imagery I am a big fan of. And the adult side might see a figure navigating through life with a black horse of shadow and instinct, anonymity and distinction, both seen and unseen.

But more than aesthetic irony, this piece can be read as an act of defiance. To paint in a style that knowingly refuses sophistication is to reject the hierarchies that privilege technical mastery over emotional truth. I like to think of it as the beginner’s blessing.

The so-called “childish” aesthetic becomes a tool, a way of smuggling grief, rage, and alienation into a form legible to anyone, regardless of their fluency in the art world’s codes. It says: You don’t need to be trained to speak; you only need to have something to say.

Perhaps that is what I meant when I began this whole BABY series, I meant to find a a way to remind myself of the this blessing, to return to how I first learned to paint, to remember what makes me different.

In this way, the painting becomes a form of personal reclamation. The figure doesn’t hide from the label; it rides beneath it, hands raised, stars branded into their skin like constellations they own. The horse carries them forward, not toward redemption or acceptance, but toward a place where insult becomes identity, where illegitimacy becomes freedom. Toward maturity.

Some say that as we grow older, we find more ways to bring out the child within us, more ways to hold hands with the innocence of what we once were, and how we once saw the world. I hope that whenever I feel like I’m close to forgetting, I remember to paint another Baby.